My name is Sarah Berger Richardson. I am a professor of law at the University of Ottawa. I specialize in agri-food law and today I’m going to talk about artisanal production in Quebec and its legislative framework.

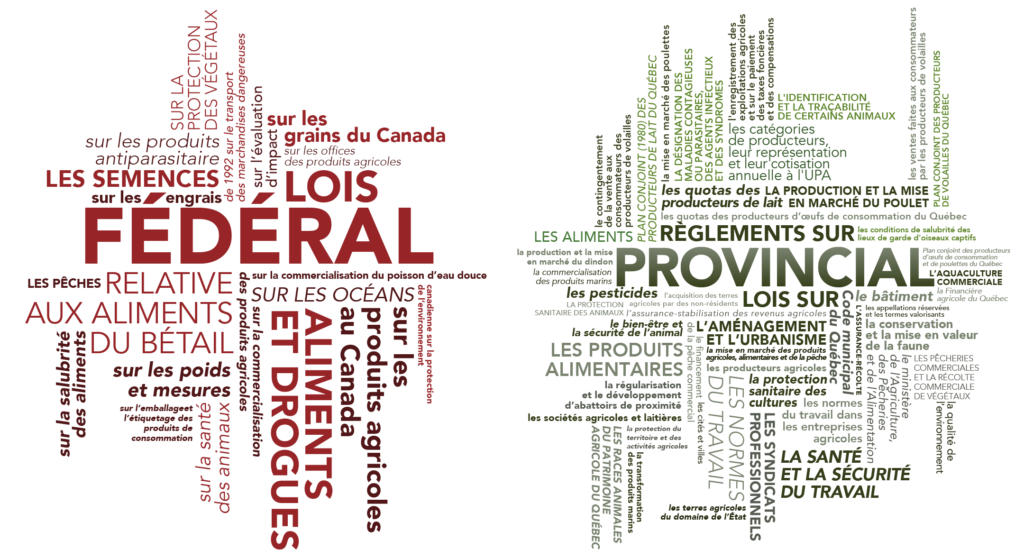

The bio-food sector is one of the most regulated sectors in Canada. Agri-food law encompasses all of the laws governing the production, harvesting, transportation, processing, distribution and sale of food products. It also includes related laws on public health, the environment, workers’ rights and animal welfare. This means that when you walk into the grocery store, there are a lot of laws and regulations behind all these products.

When I was young, I often spent my summers in Wales with my parents, and with their friends who had an artisanal farm. It was a fairly diversified farm, so they had cows, lots of sheep, ducks, chickens, hens – so several animals that they raised on their farm. I quickly realized that the meat we bought at home did not come from idyllic farms like the one I knew during my summers, but rather from industrial breeding.

It was when I watched the movie Babe when I was nine years old that I really got an image of this industrial production. It really shocked me and I told my parents that I didn’t want to eat meat anymore. During my university career, I started to question what I was eating. Were my choices really the most ethical ones or did I need to rethink my diet? Is it more ethical for me to eat avocado toast from Mexico every morning than to eat a quarter of beef throughout the year that I bought from a producer who lives 100 km away?

So I decided to put meat back into my diet. I subscribed to an organic basket with a local producer. Unfortunately, or fortunately for him, the demand was so great that there was a waiting list for his chickens. In talking with producers, with breeders, I heard that there were a lot of barriers for them, market access barriers or legislative barriers that made it impossible to meet the demand.

In 2015, Dominic Lamontagne, who is a farmer in the Laurentians, published his book La ferme impossible. In his book, Dominic Lamontagne had a lot of information and answered a lot of my questions about why some regulations are ill-suited for small-scale production. Access barriers for artisanal producers are nothing new for Dominic Lamontagne. He believes that it is important to allow, to encourage, to favour access to agricultural land for small producers who wish to provide food products to their neighbours, to their friends, in local markets – that it is important for them, and this is something he has been advocating for a very long time. Now I’ll take you to Dominic Lamontagne’s farm to explore together the legal issues surrounding artisanal production in Quebec.

Dominic: Dominic Lamontagne – I am co-owner of the Impossible Farm. We are trying to change the law so that small-scale agriculture is legalized in Quebec, that is, we want to have the right to receive people and allow them to eat what we produce. To share, finally, our interest for a human scale agriculture.

Sarah: Hello Dominic!

Dominic: Sarah! You found the place

Sarah: Yes, thank you for welcoming me to the farm.

Dominic: Thank you for making the trip, it’s a journey.

Sarah: My pleasure. So I know there’s a lot we’re going to see today. Where should we start?

Dominic: Normally, in the morning, I do my daily routine. I’ve saved a few little activities for you – we’ll start by moving the chickens. We work in mobile cages, so every morning we move them, so we can start with that.

Sarah: Okay, we’re going to go look at that.

Dominic: So the cage, our model, it’s a cage that is 8 feet by 8 feet. Like I said, it can hold up to 36 chickens. I usually keep it at about 18-20. When it’s full, you have to move it twice a day. When it’s half full like this, once a day is enough. From this place where they were yesterday, we move them here, so a new salad bar. Careful, we go slowly so we don’t knock the door down. I’m coming down slowly. So we’ve seen everyone move.

Sarah: We see the work from yesterday.

Dominic: That’s right. So there’s nothing dramatic because I don’t have many birds, but I leave them there for a short period of time. There’s nothing worse than raising poultry, I think, inside a fixed fence. People who want to raise even a dozen chickens, even to do that inside a stationary rectangle, within a few weeks, there won’t be anything interesting in there. You see there, the hens, the chickens – it’s hens and chickens actually, we have both – will eat the clover, eat the fresh grass, so that’s really their priority.

Here we have our layer hen farm. The hens, unlike chickens, will live for several years. As I was explaining, we raise them in a mobile poultry net that we will move every ten days or so. The cage of the hens, in which there are the egg-layers, which we will see later, we move every three days. The fence will be moved every ten days. The hens, as I explained earlier, what I am looking to do is to feed them with the means at hand. We are already starting to feed them sunflowers. There, the sunflower is starting to mature. The way I work to give the sunflower to the hens, since they will eat all the pieces of the flower, is that I go like this: I chop the sunflower. Sometimes I do it with three or four flowers, but this one was broken this morning. The hens will eat almost all of what we see there. They are really extremely efficient composters.

Here, obviously, it’s laying hens. In this cage, we have the laying hens. The hens, their cage, there is a door that is always open, so they go in and out. In the cage, there are perches, so the hens roost at night. They come in and roost on that. Here, in the back, we have the nesting boxes. I’m going to lift the pallet. Here, the nesting boxes are made from milk crates, like this, that we cut in front. As you can see here, we have two beautiful eggs in this nest. It’s a bit early again today. They’ll lay before noon, in the early afternoon. There are six egg laying boxes, and we get maybe, I would say, a dozen eggs a day.

Sarah: So the eggs, with the quota regulations and supply management, it’s impossible, if I wanted to buy those eggs

Dominic: Yes. Actually, at the farm, yes.

Sarah: So I could, if it was under quota, I could come and buy them, but is a farmer’s market possible?

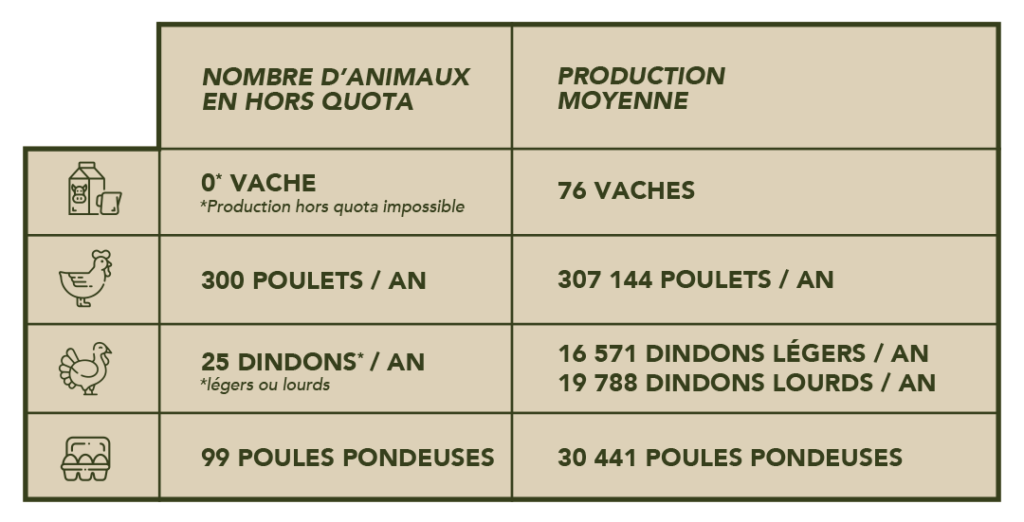

Dominic: Well, what’s happened recently, which is maybe two years ago, is that we started to have the right to sell our own eggs ourselves at farmers’ markets, which had been illegal for decades before that. But we still aren’t allowed to sell our eggs to resellers, i.e. the local grocery store. I wouldn’t be allowed to sell my eggs to a local bed and breakfast or restaurant without grading them. At the small food farm and country table level that I refer to, often, eggs, I wouldn’t say that’s our main problem right now legislatively. One hundred laying hens that we raise in an environment like this one, it’s still a job. To be able to raise as many as the commercial hatcheries, I would have to have a lot more land. It’s something I might want to do someday and would have a hard time doing legally, but for now, in a small set-up, I don’t have a hundred hens, it’s not something that restricts my freedoms more than that.

From the beginning, my concern has been the legalization of small-scale farming. So before I fight for even greater possibilities in terms of over-quota, I want to fight for the right to do something on the farm with our food. Even with a hundred chickens or a hundred hens, we can’t do much. There are three roosters here, so it’s dangerous anyway – very dangerous. Maybe we’d better get out, Sarah.

Sarah: When Dominic and his wife first started their farm, what they wanted was a diversified farm – something like the farm I grew up on, with cows, chickens, hens – a small, home-based production. They were quickly confronted by the legislative framework surrounding the marketing of agricultural products and realized that to raise cows, to raise hens, to raise chickens, that each product is governed by different joint plans, that there was a need in some cases to obtain a quota to raise their animals. There were a lot of barriers or significant costs that one has to invest in order to simply have access or the right to sell products.

We often hear about supply management, but what is it? In fact, supply management is a production quota to ensure a certain price for producers based on production costs. The idea here is to find a balance between the needs of consumers for certain products and the needs of producers to ensure a stable income. We often think of milk. Milk is something that is often in the media, but chicken is also something that is subject to supply management. That’s why I had such a hard time when I was trying to buy directly from my local organic farmer, because at the time it was limited to 99 birds a year. If my local organic farmer wanted to meet the demand, he would have had to buy quota to be able to raise and slaughter more than a hundred chickens a year.

Supply management provides some income stability for producers, but also at a price. It imposes a vision for agriculture; it imposes a specific breeding model on all producers. This excludes producers like Dominic Lamontagne, who has a different vision, a vision for small-scale production, and who is excluded from this market because of the requirements and quotas.

All producers in Quebec, whether Dominic has a small-scale farm or an industrial-scale producer, are subject to the same rules under the Act Respecting the Marketing of Agricultural, Food and Fish Products. This act exists to protect agricultural producers, to coordinate the marketplace, and also to help producers compete globally. The objective of the Act Respecting the Marketing of Agricultural, Food and Fish Products also ensures a certain food autonomy in Quebec.

With all the interest in food autonomy in Quebec, there is more and more talk about short supply chains and farmers’ markets. Short supply chains, essentially the idea of shortening the food chain between the consumer and the producer, is something that interests Dominic Lamontagne. He talks about it in his book and he has a lot to say about it.

Sarah: There were different breeds of chickens, so it’s diverse in that respect. I know we talk about diversified farms, multi-producer farms, generating farms – your farm, how would you describe it?

Dominic: It’s a bit of everything. Those are words that come and go. There are fads in there, but I think the concept of a diversified farm, or as you said “multi-producer”, is a farm that is, first and foremost, a form of, perhaps, food-prioritized agriculture. That is to say, I think that a farmer’s first objective should be to feed himself with a variety of foods. When you fall into monoculture or mono-farming, you can’t even feed yourself. What exactly are you building? Just a business or a nurturing environment? I think what has happened to agriculture, when you talk about conventional agriculture, productivism, the farm that I call on intensive care, is that you produce a commodity in large quantities and you are very dependent on a wide variety of inputs. I think this happened when we decided to professionalize agriculture. In the 1950s, that was literally what the UPA announced in the La terre de chez nous. They said, we want to make agriculture a closed profession where only real farmers would be allowed to practice. That, obviously for me, is an offensive formulation. I think that when we decided to stop producing a variety of products on the farm, that is to say eggs, milk, meat, and we decided to produce just one thing, that we cut the link with the customer. I think that’s where the perversions that we recognize in industrial agriculture today are born. For me, the diversified farm is the one that has the most difficulty existing today given the legislative context. As I often explain, having two cows, 200 hens and 500 chickens, we’re talking about $308,000 in quotas, but after that, we’re talking about another $700,000 in infrastructure to have the right to make something as silly as a chicken pie. That is, if you want to make a chicken pie with your eggs, your butter, your chicken, you have to have a slaughterhouse nearby, a dairy plant. I feel that agriculture has lost its identity by concentrating like that and bringing in the idea of working in silos. Me, by raising, seeing to the feeding, and then slaughtering the animals, I accompany them from A to Z in all that. Obviously, I don’t want to be slaughtering all the time, I don’t want to be doing this or that all the time, so for me it moderates my own transportation.

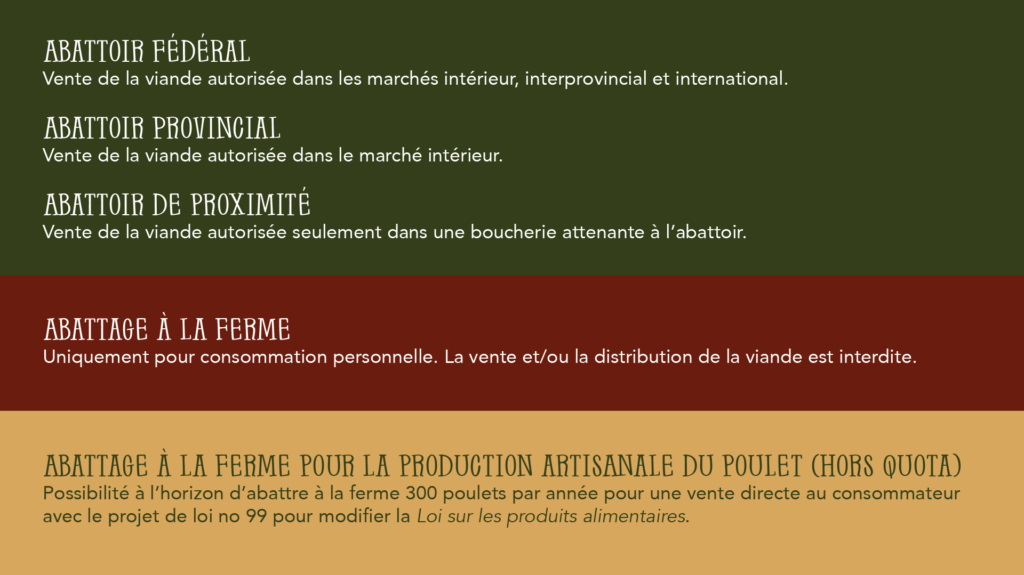

Sarah: In Quebec, in order for a producer to sell his meat, he must go through a slaughterhouse under permanent inspection, either federal or provincial. For some producers who want to sell in short supply chains and directly to consumers, the need to go through a provincial or federal slaughterhouse under permanent inspection is a barrier. This is the case for Dominic Lamontagne, who would like to raise his animals on his farm and slaughter them on the farm to sell the meat or processed products directly to his customers. The Quebec government is increasingly recognizing the importance of encouraging artisanal production in the province. For this reason, MAPAQ recently launched a pilot project to allow producers like Dominic Lamontagne to raise chickens on his farm and slaughter them for sale to his customers. This pilot project could eventually lead to an amendment to the Food Products Act creating a fourth category of slaughterhouse in the province. In addition to the federal, provincial and local slaughterhouses, there will be a fourth category for artisanal production: on-farm slaughtering.

Dominic: Here, Sarah, I have a chicken catcher. No, I didn’t make it myself. It’s a chicken catcher, so you catch them by the legs. Before you slaughter a chicken, you have to fast it for 24 to 36 hours, so obviously the gutting is cleaner. But that allows me to say that fasting, once every ten days I would say, for any animal that is being slaughtered or not, is not bad. So this is the stage that the chicken likes the least. Notice the screaming that it does. We explain that to our workshop participants all the time. When I caught him, he was screaming, he was yelling, so he’s able to express himself when he doesn’t like it. But when I go to slaughter him, he doesn’t say a word about the game. So in the context of the pilot project, we are asking MAPAQ to allow us to slaughter small quantities of poultry on the farm in a slaughterhouse that we call seasonal. That is to say that it is not an establishment that operates 365 days a year. It’s an establishment that allows us to slaughter our hundred or two hundred birds on the farm to market them on the farm. We find that a chicken that has been raised on the farm, from the egg, to the chick, to the mobile cage, to the food product that we try to produce locally, we want to be able to take that chicken, to take them one at a time if we want, when they are the size that interests us, when we need to slaughter them. We want to be able to go to the slaughterhouse, that we’ll be visiting there – we’ll walk, maybe, 20 meters with the chicken to get there. After that, we want to be able to keep the feathers, the viscera and the blood to compost it, because we put these feathers, viscera and blood together with curdled goat’s milk, and we have put some pasture that we have built up slowly. A lot of effort has been put into everything that makes up the chicken you see there. There’s nothing that goes to waste. Once we have composted what we are not interested in, we use the liver, we use the heart, we use the gizzard, we use the legs, we use the bones, we use the meat, we use everything, and then we serve it on the farm. So even the residues of people’s meals, we will compost them too. For us, it’s really the A to Z, the real short circuit: a short supply chain of production, transformation, then marketing. So let’s go slaughter this rooster.

So as I was explaining to you, I do a bloodletting. So I bleed, I cut the two veins on each side of the trachea and the esophagus, without cutting the esophagus and the trachea. So the animal is not asphyxiated, it does not choke on its own blood. It bleeds, then it will die by exsanguination. The heart continues to pump, and this is what allows the blood to flow out. We have a 35% more efficient bleeding when we bleed the chicken alive. Of the hundreds of chickens I have slaughtered, I have never felt that I was inflicting any particular pain on them. You’ll see what I mean. So as I was explaining, I’ll cut on one side, I’ll cut on the other side. So you see, there were no mortal screams like there were when I took it out of its cage. You’ll see, the minute the chicken starts to struggle, which will happen in about maybe a minute, is that there, we have total loss of consciousness, and then we have the parasympathetic system coming on board. Eventually, the legs will rise, that’s the first step, so we have some small movements. There, we have something that I consider very effective. When we have these movements, the chicken is no longer with us, and when the legs have completely stiffened, I will rinse it. Here you are, Sarah, your supper. No, unfortunately I’m not allowed to make you eat it. We have a really nice chicken carcass. You see, it’s more like a Cornish hen than the classic chicken. We’ve got a really nice little rooster that we could make a coq au vin with, a chicken crapaudine – the sky’s the limit, as my grandfather would say.

The law that is at play here is essentially the Food Products Act, I think it’s chapter P-29. In this law, I think the exact words, I forget them, but basically it explains that a poultry that is going to be sold, it must be slaughtered in a slaughterhouse context that has a slaughterhouse permit. Right now, there are different categories of slaughterhouse permits, but they don’t have the category that you need, which is a category that allows you to work in a more seasonal, temporary infrastructure.

Sarah: Can we say for our audience that there are three categories in Quebec right now: the local slaughterhouse, the provincial slaughterhouse and the federal slaughterhouse. So depending on where we send the animals, we can either take them to the local slaughterhouse to have them for our own consumption, we can take them to a provincial slaughterhouse to then sell them in the province, or then to the federal slaughterhouse to sell them throughout the world. But these are not adequate solutions for you. You want something else.

Dominic: It’s like a local slaughterhouse license. If you go to a local slaughterhouse with your poultry, you can’t do anything but take it home and eat it yourself. If you build a local slaughterhouse at your home, then you have the right to sell the poultry at your home. To build a local slaughterhouse for yourself is something that costs about $400,000. For a local slaughterhouse. So what I want is to be able to allow an artisan to invest $5,000 and have the right basic equipment that allows them to operate with an extremely small quantity of poultry, because we are allowed a maximum of 300 birds per year. What MAPAQ is going to come and do is observe our methods and then see if they agree with our claim that hygiene and food safety are protected. Obviously, the idea would be to amend the law so that a new category of permit exists, which could be called “artisanal slaughter on the farm” or a “seasonal slaughter”. I want to be able to keep the know-how alive, to be able to do all the steps it takes to go from the egg to the plate, if you will. The typical product I offer here, my chicken raised the way I want it, slaughtered the way I want it, prepared the way I want it. Freedom of action, then the possibility of expressing its uniqueness, its particularity.

Talking with Dominic Lamontagne and visiting his farm, we see the importance of diversity in agricultural production in Quebec. Can we develop a regulatory framework that allows artisanal producers as well as other producers who work in the supply management system, as well as producers who target international markets? Can all these producers be governed by regulations that are flexible enough to allow each one to express themselves, to respond to the demands and needs of consumers, but also to remain faithful to their own vision of what agricultural production is?

I think it’s desirable. I think it’s possible. And you, what do you think?